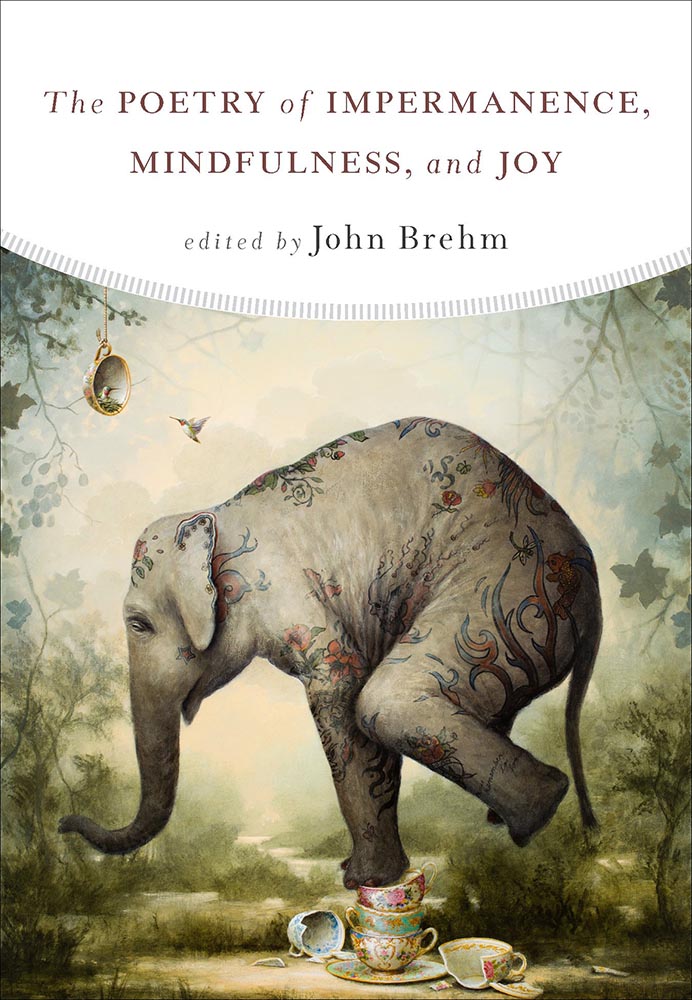

The Poetry of Impermanence, Mindfulness and Joy

2017

“While this collection would make a lovely gift for a poetry-loving or dharma-practicing friend, it could also serve as a wonderful gateway to either topic for the uninitiated.”

—Tricycle

from the Introduction

No poem can last for long unless it speaks, even if obliquely, to some essential human concern. Tu Fu’s poem about the pathos of ruins at Jade Flower Palace, which opens this anthology, has lasted more than 13centuries, reminding us that impermanence is one of poetry’s oldest themes, perhaps the oldest. Of the prince who ruled there long ago, Tu Fu writes:

His dancing girls are yellow dust.

Their painted cheeks have crumbled

Away. His gold chariots

and courtiers are gone. Only

A stone horse is left of his

Glory.

Awareness of the fleeting nature of things may well have sparked the first poetic utterance. Lewis Mumford in The History of the City suggests that the earliest human settlements arose when our distant hunter-gatherer ancestors refused to leave their dead behind. It’s not hard to imagine that such a decision may also have inspired elegiac honoring of the dead in the form of heightened speech or song-like lament, a kind of proto-poetry.

Ki no Tsurayuki in his preface to Kokin Wakashū, the first imperially-sponsored anthology of waka poetry, published in 905, observed:

When these poets saw the scattered spring blossoms, when they heard leaves falling in the autumn evening, when they saw reflected in their mirrors the snow and the waves of each passing year, when they were stunned into an awareness of the brevity of life by the dew on the grass or foam on the water…they were inspired to write poems.

“Death is the mother of beauty,” as Wallace Stevens would put it a thousand years later. There are other sources of inspiration, of course, but none more ancient or enduring than the pang that accompanies our experience of loss—and our uniquely human foreknowledge of loss.

Perhaps there is some comfort in knowing that impermanence defies its own law, is exempt from its own implacable strictures, is itself unchanging. Ikkyū states the paradox succinctly: “Only impermanence lasts.” The truth of impermanence, as Ryōkan says, is “a timeless truth.” It is not historically or culturally conditioned. It is not an idea but a process, observable anywhere at any time. Buddhist poets of ancient China and Japan may have been more finely attuned to that truth, through formal meditation practice, but western poets are held within the law of impermanence no less firmly than their Asian counterparts, and awareness that all things pass away is inescapable for anyone who pays attention. Of course, our culture encourages us not to pay attention, to live as if we will live forever, as if we can plunder the earth unceasingly and without consequence. “What dreamwalkers men become,” Master Dōgen writes.